Why should you care about the Imposter Syndrome? Perhaps you’ve never had a moment of self-doubt in your life! Chances are, though, with 70% of people experiencing it, you know what I’m talking about, or the people either side of you do!

What does that mean?

As an individual, the imposter syndrome can undermine confidence, prevent us from seeing our capabilities or recognising their value, get in the way of us connecting, engaging and collaborating. It can cause us to hide, fearing discovery. Clearly, this is not useful for the individual or those around her/him.

As a leader, if you experience it yourself, the syndrome can stand in the way of you leading others effectively. The role of a leader is to recognise, develop and inspire the talent in those we lead. However, when we feel we’re not good enough and don’t want others to find out, we’re not focussed on them. We’re focussed on protecting ourselves from discovery.

It’s likely people in your team will experience the syndrome. These will be talented people, perhaps high potentials who turn into over-achievers or simply fail to live up to their possibility. It serves you well as a leader to figure out what’s going on and how you can help them move past it.

Mindset is no longer personal and off-limits. It’s the new ‘performance frontier’ and a significant opportunity for organisations to develop the potential of its talented people.

So much is written about the imposter syndrome. People generously share their personal experiences. Coaches share their tips. In my experience, they are pieces of the total puzzle and fall short of explaining what it’s all about.

Why do we experience the Imposter Syndrome? Why does it seem to impact some people more than others? What happens when we do experience it? And what can we do when it hits us both in the moment to relieve the pressure and in the longer term to diminish its impact on our lives, careers, businesses.

In my experience, the Imposter Syndrome is a case of mistaken identity. It is a belief about who we are, how worthy and valuable we are as human beings. When we experience the Imposter Syndrome, we feel that we’re not good enough.

These are the symptoms you are likely to experience:

- Feeling like a fake or fraud

- Focussed on your weaknesses and failures rather than your strengths and successes

- It is likely you are unable to even see your strengths. However, if you can see them, it’s likely you don’t see their value, thinking that if you’re not good enough, everyone must have similar strengths. They must be common. They can’t exactly be rocket science.

- If you are successful, you attribute those successes to good fortune or someone else’s mistakenly positive view of you

- You may be unable to deny your role in the success. In this case, you may worry that you can’t pull the rabbit out of the hat again.

In 1978, Dr. Pauline Rose Clance and Dr. Suzanne Imes identified the Imposter Phenomenon after researching 150 talented and high achieving academics. The syndrome had first been identified in final year female Masters or PhD students. These women were concerned they would fail, even though they had only received Distinctions and High Distinctions in their academic careers.

They found that 70% of the women they researched had experienced the Imposter Syndrome and 33% of the subjects experienced it intensely and frequently.

Take a similar test to see if you experience the Imposter Syndrome.

As with most things human, the cause of the Imposter Syndrome is a combination of nature and nurture.

Briefly.

Nature: More than 50% of our personality comes through our DNA. The 5 Big Personality Factors are:

- Agreeableness (trust, kindness, altruism, co-operation)

- Extraversion (excitability, sociability, assertiveness and emotional expressiveness)

- Openness (imagination, insight, curiosity)

- Conscientiousness (thoughtfulness, good impulse control and planning)

- Neuroticism (sadness, moodiness and emotional instability)

Two factors are associated with those who experience the Imposter Syndrome.

Conscientiousness and Neuroticism.

People who experience the Imposter Syndrome have a low level of conscientiousness. They can set up unrealistic goals, give into impulses, can be disorganised, procrastinate, or fail to complete tasks.

They also tend to have a high level of neuroticism meaning they experience a high level of stress, worry, can get upset easily and respond disproportionately to events, can experience dramatic shifts in mood and can struggle to bounce back after stressful events.

Nurture. Our early conditioning sets up the way we perceive and interpret the world. You probably know that before the age of 7, we have no way of filtering the messages we are exposed to. We take them in as gospel.

This is where the seeds of the Imposter Syndrome are set up.

3 characteristics primarily create the likelihood we will experience the Imposter Syndrome.

Perfection. If one or more of our parents or caregivers are perfectionists, it is likely we will internalise that drive. What this means is we hold ourselves to an idealistic notion of perfection. We are unable to describe it. We just know we haven’t achieved it. We focus on the gap between our achievement and this idealistic notion, reinforcing our feeling of not being good enough.

Criticism. Often intended to motivate, criticism reinforces the feeling of not being good enough, particularly if we have done our very best.

Labels. Primarily in families with more than one child, parents label their children with a dominant characteristic. They may find one child sporty, another creative, or intelligent. We want to please our parents. It’s a strong drive to ensure our needs are taken care of. So we do our best to live up to their label and believe other labels don’t apply to us. It takes growing up, maturing and self-reflection to discover who we are to let go of that restriction.

So both nature and nurture set up the tendency to experience the imposter Syndrome. However, it remains latent until something in our external environment triggers the feeling of not being good enough.

In our early conditioning, we develop beliefs about who we are, how worthy we are and what we deserve in life.

Those beliefs are buried deep yet still drive our interpretations of situations we’re exposed to, and our subsequent behaviours.

Our beliefs are unconscious and hard to identify. However, we can identify what triggers that belief and feeling of not being good enough.

When we understand what blindsides us, we can question the reason it has short-circuited our capabilities and confidence. We can conceptually at least identify the belief that may be driving that experience.

If you want to start this process, follow this link to access a list of work triggers.

The feeling of not being good enough can be devastating and painful. We feel as though we’ve lost control, vulnerable and exposed.

We instinctively react to minimise or eliminate that feeling.

We do one of two things.

We believe our capabilities aren’t up to standard and that’s why we feel we’re not good enough. While that can be the case, it is rarely the cause of a pervasive feeling of not being good enough.

We engage in coping behaviours unconsciously designed to reduced the feeling of vulnerability, of not being good enough and to restore a semblance of control.

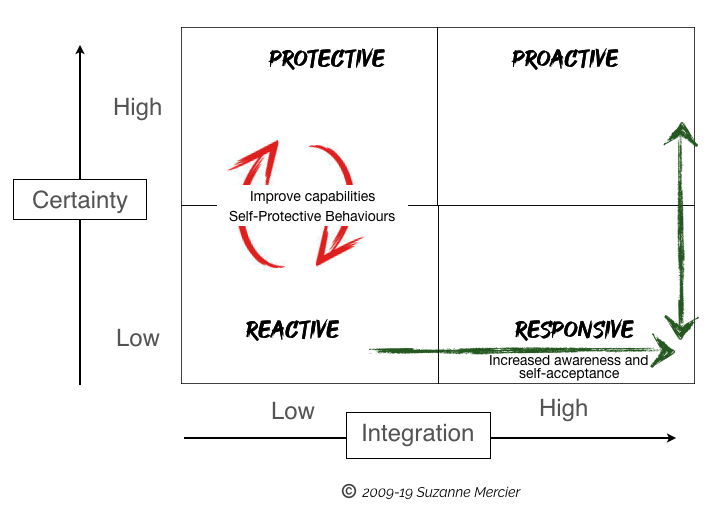

The first axis relates to the level of environmental certainty we are exposed to. High or Low.

In today’s disrupted business environment, the level of uncertainty is typically high.

So why can some people exist in environmental uncertainty and seem well able to cope?

There are many factors relating to mindset that influence our interpretation of and response to the situations we’re exposed to.

When life is ticking along nicely, the possibility of experiencing the feeling of not being good enough is latent; it hasn’t been triggered. Even so, we remain hyper-vigilant to threat.

Then if a situation occurs in our external environment that triggers a feeling of not being good enough, we react.

In our discomfort, we engage in one of the two categories of behaviour outlined above – we seek to enhance our capabilities or engage in coping behaviours.

These serve to relieve us in the moment. However, they only reduce the discomfort in the moment. They don’t solve the problem.

Interestingly, it’s often the coping behaviours that cause the problem, not the feeling itself of not being good enough.

The journey is one of self-discovery, dismantling barriers and increasingly accepting ourselves as the imperfect yet amazing beings we are.

The process of integration brings 3 factors together: How we see ourselves at 3 am; How we want others to see us; and How they actually see us.

Here are some ways to begin the process.

1. Map your mindset. Identify how the Imposter Syndrome shows up for you and the specific strategy you need to engage in to move beyond the syndrome. Areas include the specific coping behaviours you engage in, the drivers behind those behaviours, the triggers that set you off, and the beliefs that lie beneath those triggers.

2. Identify what supports your desired outcome and what stands in its way. Some of your mindset will be positive, strong and supportive. Other areas may prove to be barriers to your success. You need to identify those barriers and dismantle them.

That is the journey of increased self-awareness and acceptance.

As we progress on that journey, we move into a Proactive / Responsive space.

When all in our external environment is relatively comfortable, we sit in a space of being proactive, able to go after what we want, able to be generous to others, able to be the kind of leaders that followers are crying out for.

There’s no doubt that elements of the external world can still impact us. Instead of going into reactive mode, we are responsive, quickly recognising that we have been triggered into feeling we’re not good enough, and able to draw on the tools and capabilities we’ve developed to move back into a proactive space.

When we. no longer feel we’re not good enough, what can we do? Who can we be? How can we show up?

I think this is a lifelong journey. Having said that, we quickly see shifts in how we feel about life, how we handle the bounces when they come, how we aspire to opportunities and success.

If you can relate to the Imposter Syndrome and feel it may be holding you back, or holding back someone in your team, perhaps it’s time to do something about it?